Over the winter months, there is a sharp rise in the number of children being struck down by viral respiratory illnesses. But how do you know whether your child has a respiratory illness and if you should rush them to hospital? Parentmedic ambassador and emergency nurse Prudence Fletcher explains how to determine whether a child needs medical attention.

I have been an emergency department nurse for almost 10 years. I know from experience that each year as we come into winter, with the changes in the weather, we see an increase in presentations of children with viral respiratory illnesses. Some children are only mildly unwell, while others are very unwell and require immediate medical intervention.

A common theme I have noticed over the years is that parents are unaware of the key red flags associated with viral respiratory illnesses and often underestimate their gut instinct. Here I share they key red flags to look out for, which will hopefully make you more confident in identifying a respiratory illness in your child.

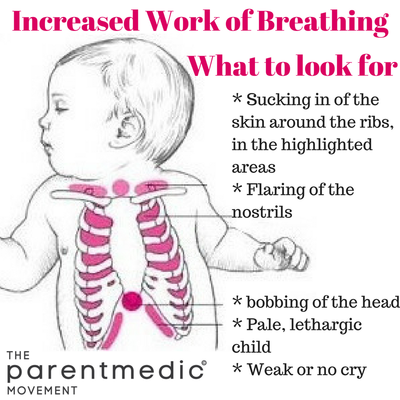

When a child becomes unwell with an illness affecting their lungs they will become short of breath. Their breathing rate will increase as will their effort required to breathe – we call this ‘increased work of breathing’.

When looking for signs of ‘increased work of breathing’, it’s important to remove all clothing from the chest area and look for sucking in of the skin around the ribs. If you can clearly see the definition of the ribs with each breath then the child is having to work really hard to get each breath.

With an unwell child we also look at how the child is interacting. A child who has a respiratory illness but is still running around and happy is usually safe to be assessed by your GP. But a child who is flat and lethargic with a weak cry is very unwell and needs medical attention immediately.

Two of the most common respiratory illnesses children get during winter are croup and bronchiolitis. The biggest thing to note about croup and bronchiolitis is that they are viral respiratory infections and therefore antibiotics won’t help.

Croup is a viral infection that causes swelling and narrowing of the airways. It is characterised by a hoarse voice and harsh barking cough, usually described as sounding like a seal barking.

In mild cases of croup, a child will just develop the cough and no other symptoms. As long as the child is comfortable, there is nothing that needs to be done other than let the illness run its course which usually takes 3-4 days.

In severe cases of croup, a child can develop a stridor, (high pitched noisy breathing that occurs when they are at rest).

A child with croup needs to see a doctor if they develop a stridor, ‘increased work of breathing’ or are distressed and unable to be consoled. If the child is well, comfortable and managing to keep their fluid intake up they can be managed at home for the duration of the illness.

Croup usually only affects children up until the age of five, although can be experienced at older ages in rare cases.

Bronchiolitis is another viral illness that can affect a child’s breathing and is most common in babies under the age of one.

Bronchiolitis usually lasts about 7-10 days with the child usually at their worst around day three. It starts as a cold and cough, and will develop with wheezing, a fast respiratory rate and ‘increased work of breathing’. Medications will not usually help bronchiolitis – it is just a matter of letting the illness run its course.

The best thing for babies with bronchiolitis is to offer smaller feeds more frequently. The illness causes congestion which makes breathing and feeding at the same time difficult, and therefore they tend to tire easily while feeding. This means they don’t drink as much and are at risk of becoming dehydrated.

Babies with bronchiolitis that have ‘increased work of breathing’ and are having difficulty feeding will need to be admitted to hospital and will often require a small tube to be inserted in their nose, down to their stomach. This is called a nasogastric tube and gives extra fluids to prevent the baby from becoming dehydrated.

If at any time you, as a parent, are concerned about your child – even if they are not displaying the characteristics mentioned here – please seek medical advice.